Partners:

OCHA Cameroon, WFP Cameroon, FAO Cameroon, Cameroon's National Observatory for Climate Change (ONACC)Summary:

In August 2024, flooding in the Far North Region of Cameroon reached unprecedented levels. Nearly 450,000 people were affected, with over 56,000 homes destroyed. Tens of thousands of hectares of crops were lost—a devastating blow to a population heavily reliant on agriculture and already struggling with insufficient access to food. The flooding during the April to October rainy season was the most severe since records began in 1998.

The humanitarian community in Cameroon is determined to mitigate the impact of floods and droughts on people’s lives and livelihoods, but getting ahead of climate disasters is challenging. Forecasts can be unpredictable and often lack the analysis needed for humanitarian decision-makers to identify who will be affected and where to deploy resources. In 2024, the Centre for Humanitarian Data supported OCHA’s Cameroon Office, the Food Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Food Programme (WFP), with flood impact analysis ahead of and during the April-October rainy season.

Insights from the Centre’s analysis enabled the launch of several anticipatory action projects that helped protect homes, schools and marketplaces before the peak flooding. The initiative also boosted confidence in the use of predictive analysis to anticipate the impacts of floods and droughts on vulnerable communities in Cameroon. Now the humanitarian community in Cameroon is making risk analysis a core part of humanitarian planning, including in the 2025 Humanitarian Response Plan, to support earlier responses to extreme weather events in the future.

Challenge:

In the Far North Region of Cameroon, rising temperatures, persistent droughts, and desertification are putting communities at risk. Water scarcity is forcing people to move closer to rivers, where they face increased exposure to floods. Overall rainfall may be decreasing, but the frequency of heavy precipitation days is rising, leading to devastating floods that destroy homes, schools, livestock and crops.

Benedetta di Cintio, OCHA’s Head of Coordination in Cameroon, has managed flood responses in eight countries. Reflecting on her arrival in Cameroon in late 2023, she said: “When I came to Cameroon, I was told to expect severe flooding every two years. I did not want to simply wait and watch it unfold. If humanitarians could act early and support people to protect their lives, homes, and incomes, then I had to see if it was possible.”

However, transforming the likelihood of severe flooding into actionable analysis that humanitarian decision-makers can trust is no small task. Weather forecasts alone often lack the necessary insight for effective humanitarian planning.

“In the past, I regularly received weather forecasts, but it was hard to know what to do with the information. To plan effectively, humanitarians need to understand how many people might be impacted, where, and with what certainty, but such analysis was hard to come by,” said Ms. di Cintio.

The lack of accessible, actionable analysis often leads to reluctance or skepticism among humanitarian actors. As Ms. di Cintio explained: “Forecast information can be filled with technical jargon and probabilities. At best, it’s daunting to understand; at worst, it’s easily dismissed as unreliable. With limited resources, the tendency is often to wait and see if the event materializes.”

While more organizations recognize the need for acting early and are using climate science, the information often remains siloed within individual agencies. According to Ms. di Cintio: “For action to happen at the necessary scale, information must shift from being held by individual organizations to being collectively owned, understood and acted upon.”

Outcome:

OCHA’s commitment to anticipatory humanitarian action motivated the Cameroon office to take decisive steps. Prior to the floods, in March 2024, OCHA Cameroon formed a small working group with WFP and FAO to monitor forecasts for the April-October rainy season. Since 2022, both WFP and FAO had begun actively monitoring rainy seasons in Cameroon, with FAO piloting small-scale anticipatory action projects.

“Coordination was key,” said Mr. Abdoulaye Imalan Boukary, FAO’s Emergency Coordinator. “Getting the attention of decision-makers and mobilizing the humanitarian community required a core group looking at the same information and collectively deciding when to ring the alarm bell.”

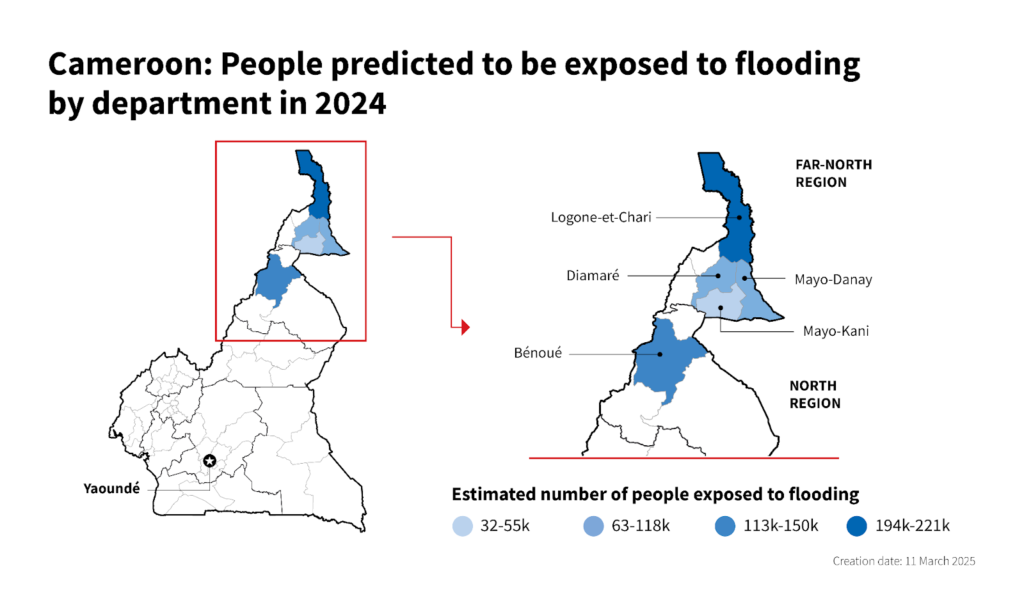

To translate weather forecasts into actionable information, the Cameroon working group collaborated with OCHA’s Centre for Humanitarian Data, which provides predictive analysis to OCHA offices globally. Beginning in March 2024, the Centre analyzed weather forecasts, including from Cameroon’s National Observatory for Climate Change (ONACC). They combined 2022 flood impact data with over 20 years of satellite-derived flood extent data to develop projections on how many people could be exposed to floods in the Far North Region.

“The Centre’s analysis was invaluable. It made the weather forecasts actionable. Humanitarian organizations could better plan where to deploy resources when forecasts indicated a high probability of flooding,” said Mr. Cedric Matsaguim, Geographic Information Specialist at WFP.

In July, the Centre projected a slightly rainier-than-normal season over the Logone and Chari River basins, with an estimated 462,000 people potentially exposed to floods in the Far North Region from the beginning of July until the end of the year. While the level of projected excess rainfall was minimal, the number of potentially exposed people was very high.

With awareness raised, the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) began implementing smaller-scale anticipatory action projects. For example, FAO used the insights provided by the Centre, along with the seasonal forecast of ONACC, to consult with community committees in Blangoua, Makary, Kousseri and Logone Birni. Thanks to funding from the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, FAO supported community plans to construct dykes to protect homes, schools, agricultural lands and market places, and pre-positioned vegetable seeds, agricultural tools and non-food item kits within these communities.

With awareness raised, the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) began implementing smaller-scale anticipatory action projects. For example, FAO used the insights provided by the Centre, along with the seasonal forecast of ONACC, to consult with community committees in Blangoua, Makary, Kousseri and Logone Birni. Thanks to funding from the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, FAO supported community plans to construct dykes to protect homes, schools, agricultural lands and market places, and pre-positioned vegetable seeds, agricultural tools and non-food item kits within these communities.

By August, rain had begun to cause flooding, impacting around 450,000 people. This closely matched the Centre’s July projections for how many people could be exposed to flooding (around 462,000 people). The HCT, now more confident in the early warning and impact analysis, asked for regular updates to further inform and reinforce the coordinated flood response.

Conclusion:

Helping communities before floods peak gives people greater self-reliance and more dignity. People have the opportunity to protect their homes and livelihoods, to pre-stock food and access to clean water, and to ensure children can continue their education.

In 2024, OCHA, supported by FAO and WFP, demonstrated how risk analysis can be used to create a shared understanding of emerging hazards and their projected impact on populations. This analysis is instrumental for humanitarians to act earlier, maximizing impact for communities and saving money.

The humanitarian community in Cameroon is now making risk analysis a central component of their planning, including in the 2025 Humanitarian Response Plan. OCHA’s Centre for Humanitarian Data will also provide similar flood exposure analysis for future rainy seasons, benefiting from additional impact data from the 2024 floods. Coordination efforts will also expand to include more humanitarian and government partners.

The Centre is working on similar risk and impact analysis to help communities prepare for floods and droughts in other countries, including Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Chad, the Central America Dry Corridor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia and Niger.