Summary:

More than 2 billion people worldwide have no Internet access or digital literacy. They are cut off from information that could help them to access essential services, improve their livelihoods, and prepare for and adapt to climate and economic shocks.

This digital divide is worse for people living in poverty, in crisis-affected countries and in remote areas, especially women. But OCHA’s Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) is helping to resolve this by making humanitarian data easier to find and use.

Sauti, a non-governmental organization in East Africa, uses HDX to access trusted datasets, including market prices, exchange rates, food security and climate data. It translates this information into short, simple messages in local languages, and delivers it to basic mobile phones via USSD, SMS and WhatsApp. No Internet or smartphone required.

Sauti’s platform is used by more than 150,000 farmers and small-scale traders across Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, most of them women with low digital literacy and Internet connectivity. People use the platform to make informed decisions about where to sell and buy their goods to avoid exploitation, plan routes that reduce food spoilage and locate nearby health services. With support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the platform will soon expand to support thousands of displaced women in Somalia, offering information on where to access local humanitarian and health services.

Sauti proves that data gives people dignity, choice and self-reliance. This reflects the heart of the Humanitarian Reset: a shift towards a humanitarian response that is locally led and globally supported, where power is transferred to local responders and affected communities wherever possible, using shared services, including common data systems.

Challenge:

More than 90 percent of people in high-income countries have Internet access, compared to less than 30 percent in low-income countries. For example, only 27 percent of people in Somalia use the Internet, and less than 12 percent have access to the Internet at home.

Limited network coverage, low digital literacy and high Internet costs prevent many people from accessing information that would help them make crucial, sometimes life-changing, daily decisions.

Around two thirds of women in East Africa trade staple food crops to support their livelihoods. These women power local economies, yet they often lack access to information that would help grow their businesses and avoid exploitation.

In Somalia, women and girls have been isolated for decades due to displacement, marginalization and poor infrastructure, but also due to gatekeepers: self-appointed individuals who control the flow of information and restrict access to vital services and assistance.

As a result, many women are left with vital, unanswered questions: What market offers the best prices for my goods? Where can I buy cheaper food? Will flooding affect my trade routes? Where is the nearest health clinic? Without this information, women are exposed to lower incomes, compromised safety, wasted food and lost opportunities.

Despite poor Internet connectivity, mobile phone ownership is high across East Africa. For example, 85 percent of people in Somalia own a mobile phone, even though fewer than 30 percent use the Internet. Sauti recognized this opportunity and set out to close the information gap for rural, women-led businesses and displaced women in East Africa. It developed a platform that would deliver information directly to people’s basic mobile phones using USSD, SMS or WhatsApp.

This process was not easy. Sauti needs market prices, exchange rates, climate forecasts, Government services and humanitarian datasets, but it takes time and resources to find, verify, clean and update all these datasets.

Lance Hadley, Sauti’s Chief Executive Officer, explained: “For a small organization like Sauti, finding relevant and credible data sources and then building the automated pipelines to clean and update datasets takes considerable time and resources. For example, we recently had to analyse 6,000 days of precipitation data to establish a baseline to support seasonal early warnings.”

The challenge is not just about delivering the information, it’s about finding trustworthy, timely and relevant sources that reflect the daily reality on the ground, and then turning disparate, technical data into something people can use to make decisions.

Outcome:

To help bridge the data gap, Sauti turned to HDX, an OCHA-managed open data platform that hosts more than 18,000 datasets from more than 200 organizations, covering 250 countries and territories. Since 2014, HDX has functioned as a common data service for the humanitarian community and beyond, making disparate data easier to find, access and use.

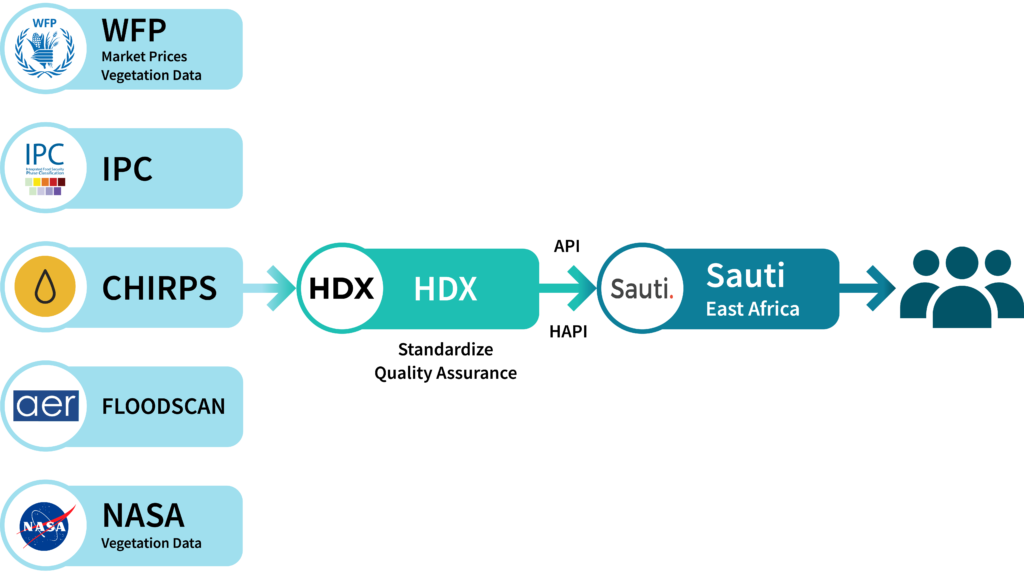

HDX is critical to Sauti’s success. It provides approximately 50 percent of the data Sauti uses for their Somalia platform, and 25 percent of data for their Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda platforms. The data they ingest from HDX includes market prices from the World Food Programme (WFP), food security data from the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), near real-time and historical flood mapping from FloodScan, rainfall data from Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station (CHIRPS), and vegetation data such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index.

Mr. Hadley added: “HDX has been a data broker for us. It reduced the burden of sourcing and verifying relevant data, transforming it into clean, accessible data we can trust. For example, there are many flood-mapping tools available, but the fact that HDX had identified FloodScan gave us confidence to use that as a source. Using HDX data gives us the assurance we need to share that information with people, knowing their choices and incomes depend on it.”

How it works

To access the data on HDX, Sauti uses an Application Programming Interface (API) – a feature that allows computer systems to exchange information on a set schedule. Sauti also uses HDX’s Humanitarian API (HAPI) to retrieve standardized humanitarian indicators. APIs eliminate the need for manual downloads and comparisons; data is automatically assessed against Sauti’s existing database four times a day and updated as needed.

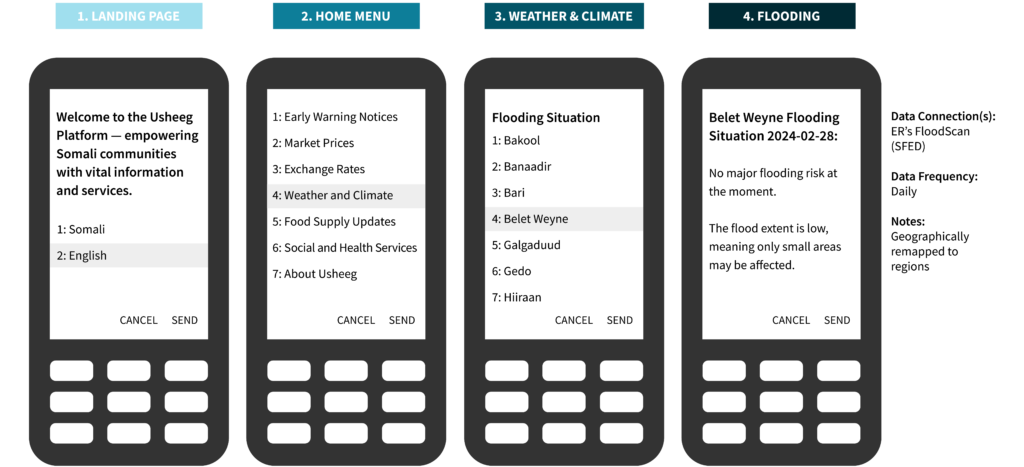

Once retrieved, the data is translated into five local languages and simplified into actionable insights. For instance, FloodScan data measures surface water coverage over a 10 km² area and compares it to a baseline. Sauti converts this technical data into simple messages, such as “Moderate flooding at [location]” or “Severe flooding at [location].” Similarly, CHIRPS rainfall data and short-term forecasts are translated to phrases such as “Rainfall is average” or “Rainfall is significantly above average.”

Sauti also enriches the data from HDX with complementary information that helps users with their decision-making. For example, WFP’s market price data may list the cost of dry maize in Mogadishu in Somali shillings, but cross-border traders might need to know the price in their local currency or compare it to prices in neighbouring markets. Sauti adds this contextual data to help their communities understand the price and decide where to buy or sell and in which currency.

This information is delivered through Sauti’s mobile platform for free using a simple number-based menu that guides users to the insights they need.

Impact

Farmers and traders have negotiated better prices, made a profit and avoided exploitation, all thanks to consistent, open access to WFP’s market price information and exchange-rate data. Users of Sauti’s Kenya platform report a 17 percent increase in monthly profit (US$29 a month), or enough to cover secondary-school fees, uniforms and supplies. Many users have diversified their business, buying and selling nearly 20 percent more types of goods to build resilience in uncertain markets.

People also use the platform to plan household food spending and assess food supply. It can be difficult to confirm that an area is in a food-insecure region, but verifying rumours with official humanitarian assessments, such as the IPC’s, enables households and small traders to prepare for shortages, avoid price shocks and seek support from local humanitarian organizations.

Climate data is also improving people’s lives. Pastoralists use CHIRPS rainfall and crop health data to plan where to put their livestock and avoid overcrowding. They also use it to plan migration, conserve water or seek aid during droughts.

CHIRPS precipitation and FloodScan data also help traders adapt their travel based on weather, enabling them to plan and buy and sell in different markets, reducing food spoilage. Families use the data to plan for disruptions with transport or markets, minimizing economic and safety losses.

Through the connection with HDX, Sauti was able to expand its services into Somalia via a partnership with IOM. Sauti aims to help 1,850 displaced women, potentially reaching up to 20,000 people before the end of 2025. Sauti is also developing a social-services section, and aims to draw on data from OCHA’s ‘Who is doing What, Where’ (3W) dataset for Somalia, making it easier for women to find nearby humanitarian and health services in their local language and reduce the risk of exploitation.

Teresa Del Ministro, IOM’s Senior Resilience and Displacement Coordinator in Somalia, said: “HDX was invaluable. As a long-standing partner of the platform, IOM could feel confident that by using the data on HDX, Sauti would be able to deliver timely, credible and relevant information to some of the most marginalized and information-restricted women in Somalia.”

Conclusion:

OCHA launched HDX in 2014 to make humanitarian data easier to find and use across organizations and crises. Since then, the platform has become a cornerstone of the humanitarian data ecosystem. Over 200 organizations share their data through the platform, and new sources are being added all the time.

Although HDX was not explicitly designed to deliver data directly to people affected by crises, the example of Sauti shows how a trusted data service strengthens decision-making at the institutional level, while also helping people in low-income and crisis-affected countries make their own decisions.

Imagine the impact if more people in humanitarian contexts could make informed choices thanks to data access. Common services like HDX can make this possible. To realize this vision, we need a better understanding of people’s questions and the data available to answer them. We also need data that is as real time and location specific as possible.

Sauti analysed nearly 20,000 listener messages from Radio Ergo, a Somali station that broadcasts humanitarian information and collects community feedback, to identify information gaps. Nearly half of the messages focused on drought, floods, rainfall and water scarcity, followed by questions about pests, locusts and other infestations.

New sources of data on infestations could let farmers better assess risks and protect their crops and livestock, protecting vital sources of income. Climate and food security data from IPC and FloodScan are useful, but more frequent updates could improve people’s ability to make everyday decisions. FloodScan’s daily satellite-based mapping of surface water is useful for tracking flood trends, but its detection is less effective in dense urban areas and can miss sudden-onset events, such as the flash flooding that struck Mogadishu on 11 May 2025. To address this, Sauti used HDX data on prolonged and extreme rainfall indicators for urban regions. But as these are updated only every 10 days, short-term, sudden-onset events go largely undetected.

To unlock the full potential of data for better decision-making, continued investment in HDX and the organizations collecting data is essential. HDX and Sauti demonstrate what is possible when data is openly available and serves people: it informs, it empowers and it changes lives. Let’s keep investing in that future.

Download the full story here.