Partners:

UNICEF, WHO, United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund, DRC National Programme for the Elimination of Cholera and the Control of Other Diarrhoeal Diseases (PNECHOL-MD)Summary:

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), cholera remains a deadly and recurring threat. But with timely action, cholera outbreaks can be contained. Over the past three years, the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) has funded an innovative approach that helped stop outbreaks before they spiral—one that is proving both life saving and cost effective.

In 2025, CERF released $US750,000 twice—in March and again in May—to respond to rising cholera cases in the provinces of North Kivu, Maniema, and Tshopo. These allocations build on a 2023 pilot in which CERF provided $1.5 million as cases increased in North Kivu, South Kivu and Tanganyika. The 2023 funding enabled humanitarian partners to quickly reach over 450,000 people with safe water, rapid treatment and health services. The result: lives saved, outbreaks under control, and resources used early when they were most effective and less expensive.

“In a resource-constrained environment, reducing humanitarian needs is more imperative than ever. This means not only responding to acute crises but also preventing them and addressing their underlying drivers,” said Bruno Lemarquis, the UN’s top humanitarian official in the DRC. “Anticipatory action is a vital part of the humanitarian toolbox. For example, it can help prevent a large-scale cholera outbreak before it escalates – saving lives and significantly reducing emergency response costs.”

The DRC’s experience is more than a success story. It is a proof of concept and a call to action for governments, donors and humanitarian actors to rethink what is possible. Because when it comes to cholera—and many other preventable diseases—waiting for a crisis to unfold is not just more deadly. It’s expensive.

Challenge:

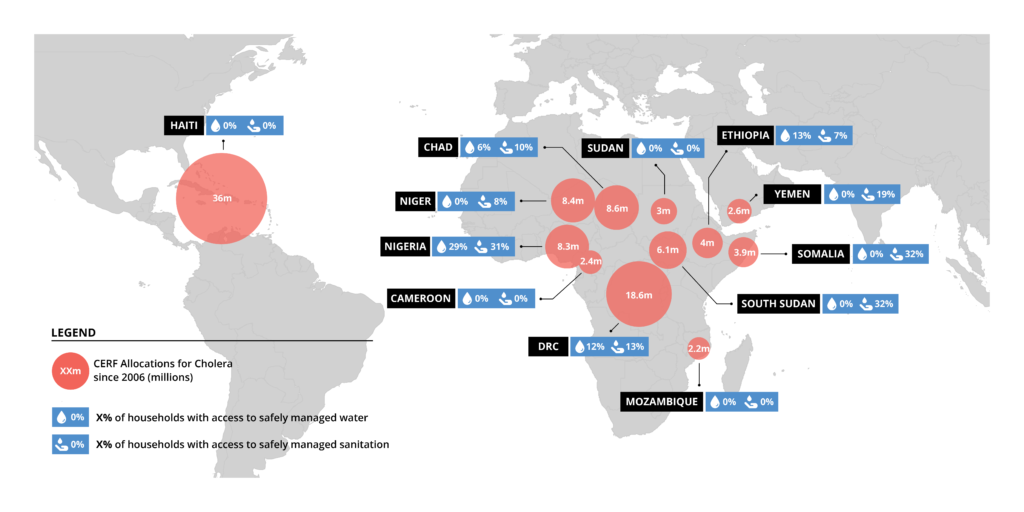

Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal disease that can kill within hours if left untreated. But it is preventable. With access to safe drinking water and sanitation, communities can be protected. However, for many people in crisis-affected countries, these essentials remain out of reach due to poverty, conflict, forced migration and fragile health systems. In these contexts, climate-related disasters, like flooding, also create the ideal conditions for cholera to thrive.

In countries with UN-coordinated humanitarian plans, fewer than 5 percent of households have access to safe drinking water. Sanitation coverage is only marginally better. In many of these places, cholera is not just a health risk; it’s a recurring crisis.

Despite the known risks of cholera, prevention efforts remain drastically underfunded. In Africa, national cholera plans receive only about 16 percent of the funding they require. As a result, humanitarian response typically begins only when outbreaks have become epidemics, when it’s harder to contain, deadlier for those affected and more expensive to manage.

Cholera spreads quickly, making a rapid response essential. When action is taken early, while case numbers are still low, deaths can be prevented and outbreaks contained at minimal cost. Oral rehydration salts cost just six cents. A single dollar can purify 250 litres of water. Research shows that up to 40 percent of deaths could be avoided with earlier intervention.

One key barrier to timely response is limited access to local data. Epidemiological case data is typically published only at the national level—showing total cases across the country—rather than capturing when cases first begin to rise in a specific community. As a result funding is often released after the critical window for early, cost-effective response has closed. This delay has been a persistent challenge for CERF funding and humanitarian action.

Outcome:

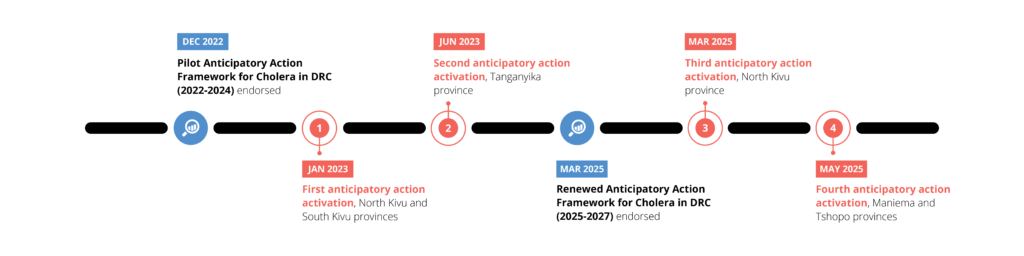

To change this, OCHA partnered with the DRC’s National Programme for the Elimination of Cholera and the Control of Other Diarrhoeal Diseases (PNECHOL-MD), UNICEF and WHO in 2022. They designed and launched an anticipatory action pilot that linked monitoring of local data with a trigger that automatically released CERF funds for pre-agreed activities, once the threshold of cases was reached.

The Emergency Relief Coordinator, the head of OCHA, pre-approved CERF to release up to $3 million in response to three scenarios: a spike in cases in cholera-prone areas, a shock such as flooding or displacement, or a rise in cases in provinces where cholera is not typically present.

OCHA’s Centre for Humanitarian Data worked with partners to develop the trigger thresholds. Weekly epidemiological data at the health zone level was shared by PNECHOL-MD, giving responders the ability to detect and act on localised risks.

In January 2023, the system was triggered for the first time in the Nyiragongo Health Zone. CERF released $750,000. With funding and response plans already in place, UNICEF, WHO, and their partners moved quickly, reaching more than 230,000 people. They increased testing, disinfected homes, improved access to safe water and sanitation, installed water purification plants and established 18 new cholera treatment centres. Public health messages reached over 860,000 people. These early interventions helped bring the outbreak under control and the fatality rate dropped to just 0.27 per cent—well below the global threshold of 1 per cent.

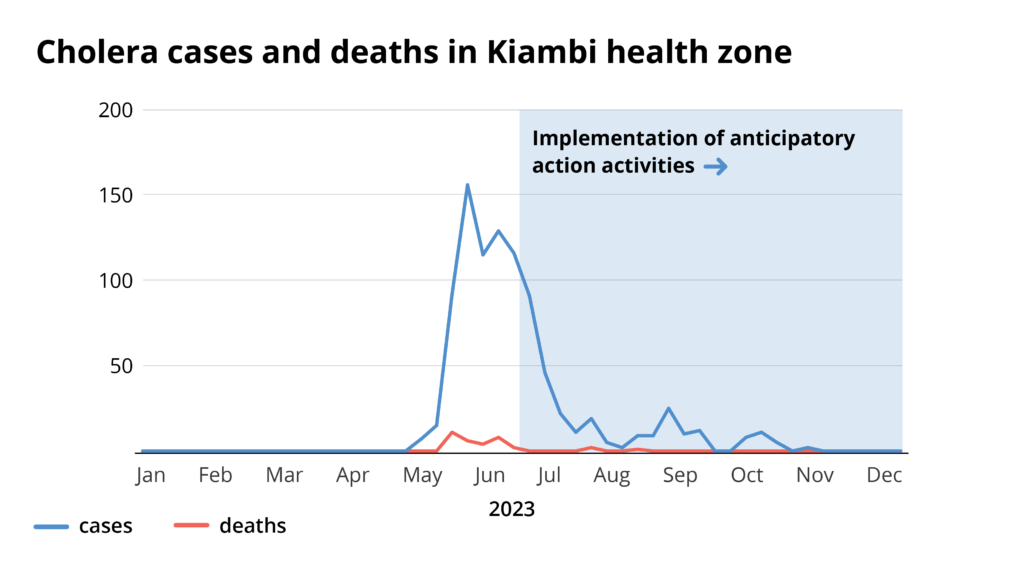

Six months later, a second activation took place in Tanganyika Province. Another $750,000 was released to support over 225,000 people across five health zones, enabling the outbreak to fall below epidemic thresholds in all zones. Communities gained access to hundreds of chlorinated water points, permanent water points were constructed near rivers and lakes, wells were cleaned, schools were disinfected and marketplaces hosted awareness campaigns. More than 5,300 people were treated in newly established cholera centres, preventing further spread and loss of life.

Conclusion:

The DRC pilot showed that anticipatory action for cholera works. Intervening before outbreaks peak not only saves lives but also reduces suffering and lowers response costs. It can even reduce gender-based risks: A 2024 study found that anticipatory action has the potential to lower risk of violence against women by avoiding dangerous journeys to collect firewood for boiling water.

The pilot also yielded valuable lessons. Triggers can be simple and don’t require a complex predictive model. Interventions are highly effective when there is a good early warning system based on timely, local epidemiological data, rapid community-based responses and clearly defined roles.

Now, the approach is being expanded. A revised anticipatory action framework was rolled out in the DRC in 2025, and similar anticipatory action plans are being developed in countries like Mozambique. OCHA and other partners, such as International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, UNICEF and WHO, are working to scale up this approach. But their efforts will succeed only if backed by political will and funding to act before diseases turn into deadly, uncontrolled outbreaks.

Now is the time to match innovation with investment—and ensure early action becomes the new standard in humanitarian response.

To learn more about anticipatory action in the DRC and lessons learned from the pilot, read the full report. To learn more about OCHA’s anticipatory action visit: Anticipatory action and Data Science – The Centre for Humanitarian Data.